Note 14. Regular Order

What is It? What happened to It?

At the center of legislators’ complaints about their institution over the past two decades has been the notion of “regular order.” The term was used for decades when legislators demanded that the rules be followed. Members of the House might yell, “regular order,” when the speaker was holding open a vote for a time beyond what is allowed in the rules. Senators would insist on regular order when he or she wanted to regain recognition to speak during a chaotic debate on the floor.

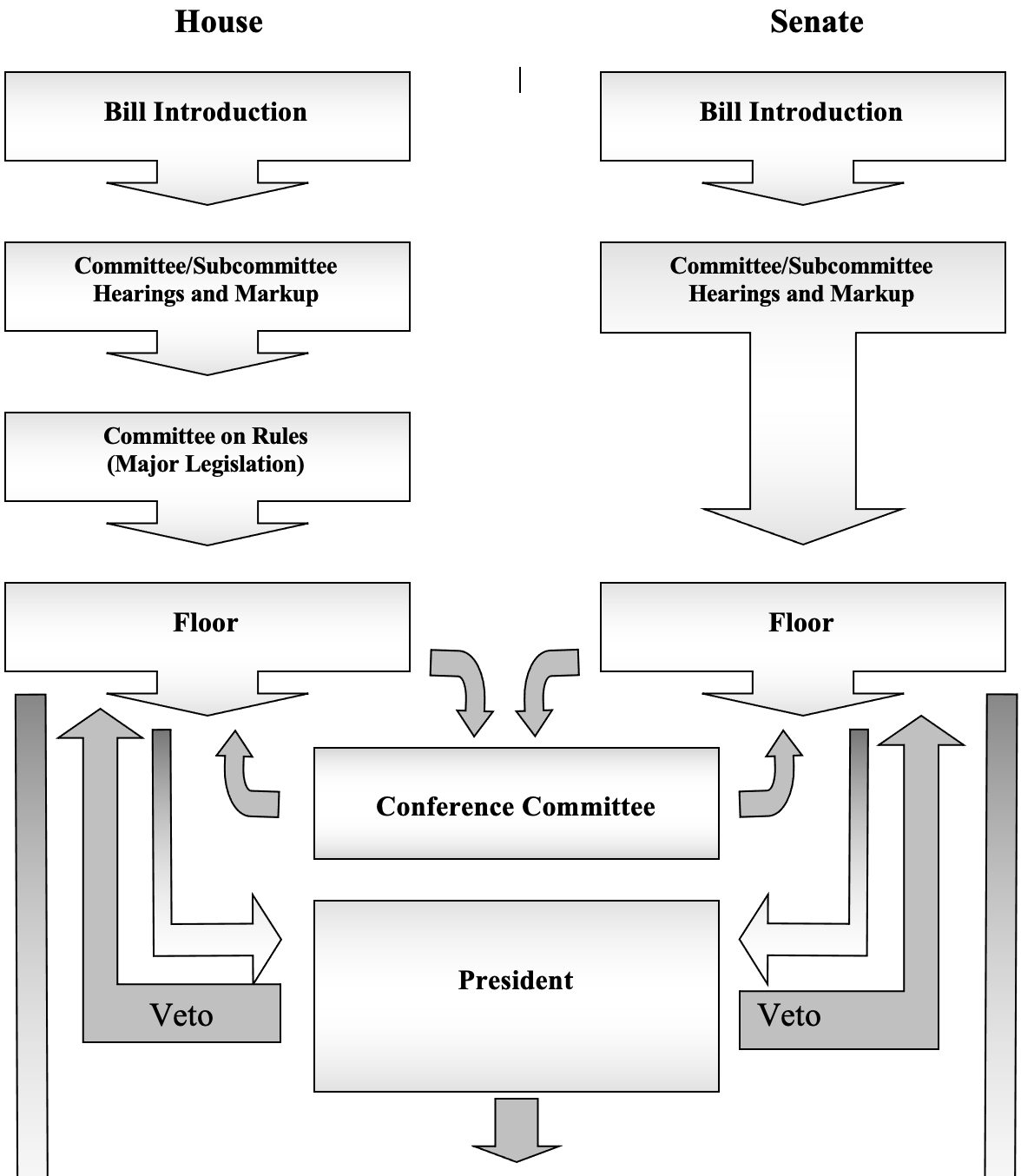

Since the early 1990s, legislators and other congressional observers began to use the term more expansively to refer to the standard, usual, or typical process for considering legislation of the mid-20th century. Political scientists have sometimes called this the “textbook” Congress—the Congress described in textbooks written the 1950s and 1960s. This is what then-House Majority Leader Richard Gephardt (D-MO) meant when, in describing how the House would use its standard committee process for considering healthcare reform in 1994, he insisted that “the regular order can work.”[1] This standard process includes referral to committee, committee hearings, markup and report, floor debate and consideration of amendments, passage, a conference committee with the other house when required, and approval of the conference report by both houses. The term is sometimes also applied to the budget process, which includes an annual budget resolution, CBO cost estimates for bills, and enactment of a dozen spending bills and additional tax bills by October 1 of each year.

I need to be clear about one thing: “Regular order” is not a term found in congressional rules or precedents. Indeed, strictly speaking, under the Constitution, the House and Senate are free to prepare legislation for final passage in nearly any way they choose. There is no “regular order” specified in the standing rules of the House or Senate. While a sequence of steps is sometimes provided in law or House and Senate rules for certain kinds of legislation, the two houses are free to modify the process. Regular order is the process that legislators still consider “normal” and it is the process found in pamphlets on “how a bill becomes a law” that Congress makes available to Capitol visitors.[2] But, in the last two decades, it is uncommon for major legislation to neatly follow the process that was common in the mid-20th century. The exceptions are so common that it has become difficult to point to any one process for enacting legislation.

Nevertheless, the regular order remains valued by many legislators. It offers opportunity for deliberation, inclusion of the minority, and consideration of alternative proposals at several stages—in committee, on the floor, and in conference. Committees are central to the standard process. Rank-and-file members contribute to the process by participating in committee deliberations, floor debate and amending activity, and conference committees, all of which is led by committee leaders who are experienced and expert.

Deviations from any part of standard processes can and have generated complaints about failure to observe the regular order. The sources of the complaints about regular order are somewhat different in the House and Senate so I describe them separately (and briefly).

In the House, the majority party sets the agenda for committee and the floor activity and makes the procedural motions that move consideration of legislation from one stage to another. As a result, it is members of the minority party and often its leadership who are the first to complain about the use of non-standard procedures. By 2005, nearly every major step of the standard legislative process was the subject of complaints from minority party members:

holding limited or no hearings and brief markup sessions;

placing control of committee agendas firmly in the hands of full committee chairs, often keeping subcommittees inactive and denying minority party members hearings for their bills;

adopting special rules from the Rules Committee that put in order the consideration of bills that were not reported by a committee;

writing special (closed) rules that bar floor amendments;

combining normally separate appropriations bills into large continuing resolutions or omnibus bills;

conducting private negotiations with the Senate to avoid conference committee;

holding “summit” negotiations among top leaders that exclude most committee members.

That is a partial list.

These features of “unorthodox” legislating began building in the 1980s under Democratic majorities, accelerated under Republican control during the 1995-2006 period, and intensified in recent years. They drew extensive attention from legislators and outside observers when they first emerged and ultimately drew condemnation in more popular accounts and commentary. In 2005, political scientist Thomas E. Mann observed that in 1995 Republican speaker “Gingrich built on [the Democrats] reforms, and [Speaker Dennis] Hastert carried it far beyond Gingrich,” leading to the “utter demise of regular order, steering policy development away from committees to [majority party] leadership.”[3] In 2018, the Washington Post and ProPublica documented these developments and reported the deep dissatisfaction they found among many, if not all, members of Congress.[4]

In the last decade or so, it has been striking that complaints about the legislative process came from members of the House majority party. These complaints have come, primarily, from small but important factions within each party. Two examples illustrate the point.

In 2009, new Democratic President Barack Obama urged quick enactment of an economic stimulus package to address the Great Recession and Speaker Nancy Pelosi responded by proposing a detailed bill before committee hearings and markups could be held, allowed only token markups, and negotiated the final details with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. The experience left moderate House Democrats, most members of the Blue Dog and New Democrats caucuses, complaining about a centralized process that left out meaningful participation by committee members.[5] Pelosi promised a return to “regular order,” but many of the complaining Democrats did not see much change. Moderates raised similar issues again in late 2018 and, as we describe below, extracted some commitments from Pelosi as a condition for supporting her reelection as speaker.

In 2015, the most conservative members of the House Republican Conference, members of the Freedom Caucus, blamed Republican Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) for deviations from regular order. In October of that year, for example, Rep. Justin Amash (R-MI) explained at a public forum in his home district that “the problem isn’t that he [Boehner] isn’t conservative enough. The problem is he doesn’t follow the process. He operated a top-down system, and still operates a top-down system because he hasn’t stepped down yet. Which means that he figures out what outcome he wants, and he goes to the individual members and attempts to compel and coerce us to vote for that outcomes.”[6] Amash was describing Boehner just two weeks after Boehner had announced his intention to resign the speakership under pressure from the Freedom Caucus. Just after Boehner’s announcement, the caucus issued a statement that it would only support a candidate for speaker who would “ensure that we follow regular order in the House and give a voice to the countless Americans who still feel that Washington does not represent them.”[7] The caucus eventually endorsed Paul Ryan (R-WI), who was elected speaker at the end of October.

The term “regular order” is used less frequently in the Senate than in the House, but in recent years it has found its way into senators’ vocabulary when complaining about developments in their chamber. The Senate story has two key elements.

The first element is the increase in minority obstructionism. Over the period since the early 1970s, the use of the filibusters, threatened filibusters, and holds altered floor decision making. In the 1990s, the minority party began to use filibusters in a more systematic, strategic way, which in turn caused the majority party to seek cloture far more frequently. In the 2000s, obstructionism intensified and frequently extended to presidential nominations to judicial and executive branch posts. This development has meant that the usual threshold for passing a bill, 51 votes or a simple majority, has effectively moved to 60 votes, a three-fifths majority, the threshold for cloture on most major legislation.

The second element is the majority party’s response. During the last four decades, the majority party’s strategies for managing minority obstruction evolved. Patience and long hours were the traditional responses, but when minority obstruction became more frequent the majority leader tried other tactics. These tactics deviate from the most common practices of the 20th century.

Filling the amendment tree has been used much more frequently since the 1990s. Under Senate precedents, only a limited number of amendments and amendments to amendments may be pending at one time—known informally as an amendment tree. The majority leader’s right to be recognized before other senators gives the leader the opportunity to offer a series of amendments in rapid succession so that no more amendments may be pending under Senate precedents. This blocks other amendments, including amendments that may be proposed by minority party senators until one or more of the leader’s amendment is withdrawn.

Majority leaders have filled the tree more frequently for two reasons. First, the majority leader sometimes seeks to prevent the minority from forcing votes on propositions that may cause political problems for majority party senators. Second, the majority leader often does not want to give the minority an opportunity to offer amendments until the minority agrees to allow a bill to eventually come to a vote. For the majority leader, filling the tree pauses action until it can be determined that there is a way to proceed that is acceptable to both parties, but for rank-and-file senators the opportunities to offer and vote on amendments are curtailed and replaced by whatever amendments partisan negotiations allow.

Naturally, the majority party seeks to avoid minority obstruction when possible. This means using budget reconciliation bills, which cannot be filibustered, whenever possible, as has been done for tax and healthcare legislation. It also means creating omnibus measures that package what would otherwise be separate bills. These tactics, directed by majority party leaders, put party leaders in a position to negotiate critical details of the legislation, reduce the role of committee members, and shrink the opportunities for rank-and-file members to participate in debate and amending activity.

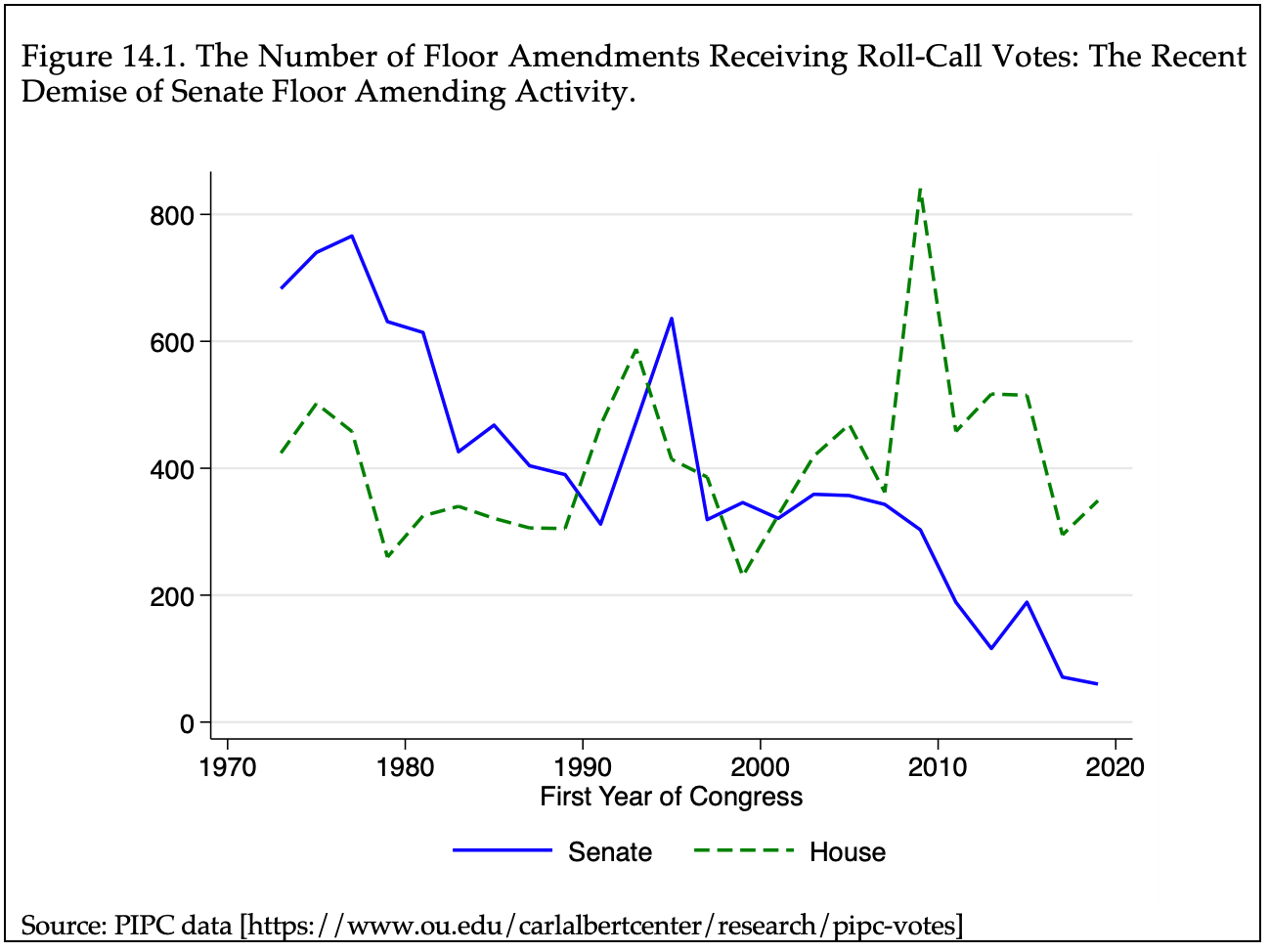

These developments have made a big difference in Senate floor activity. In Figure 14-1, the number of floor amendments receiving roll-call votes is mapped for the period since 1969. The Senate, of course, is the smaller house, but the Senate was once the house with more policy making on the floor. The combination of filibusters (reducing the number of measures debated) and filling the amendment tree (blocking the consideration of some amendments) has radically reduced floor amending activity in the Senate. It simply is not the same policy-making making body that it was just a few decades ago.

Senator John McCain (R-AZ) famously complained about several of these developments at the time he cast a deciding vote against a reconciliation bill that would repeal major parts of Obamacare in 2017. McCain said, “Why don’t we try the old way of legislating in the Senate, the way our rules and customs encourage us to act? If this process ends in failure, which seems likely, then let’s return to regular order.”[1] McCain’s comments captured the sentiments of many of his colleagues, many of whom also were advocating that the Senate return to a process in which committees do their work, minorities resist the temptation to filibuster most legislation, rank-and-file senators are allowed to offer floor amendments, legislation is not contorted to fit into reconciliation bills, conferences are used to resolve House-Senate differences, and the regular appropriations bills are passed every year. It has been many years since that process characterized how Congress handled the most important legislation.

[1] Robin Toner, “Washington Talk; Well, More than Talk: Real Votes on Health,” New York Times, March 8, 1994, p. 13.

[2] For example, see https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/about-congress/making-laws (accessed April 2019).

[3] Quoted in “Changes of ’74, ’94 Still Reverberate in Congress,” Roll Call, January 20, 2005.

[4] Paul Kane and Derek Willis, “Laws and Order,” Washington Post, November 5, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/politics/laws-and-disorder/?utm_term=.d439a6dc9aef.

[5] Tory Newmyer, “Pelosi Vows a Return to Regular Order,” Roll Call, February 5, 2009; “ Don Wolfensberger, “Democrats’ Call for Regular Order Signals Problems for Leaders,” Roll Call, March 27, 2009;

[6] Quoted in https://www.politico.com/story/2015/10/justin-amash-freedom-caucus-house-republicans-214819.[7]https://www.politico.com/blogs/the-gavel/2015/09/freedom-caucus-speaker-of-the-house-214115

[7]Congressional Record, July 25, 2017, S4169.