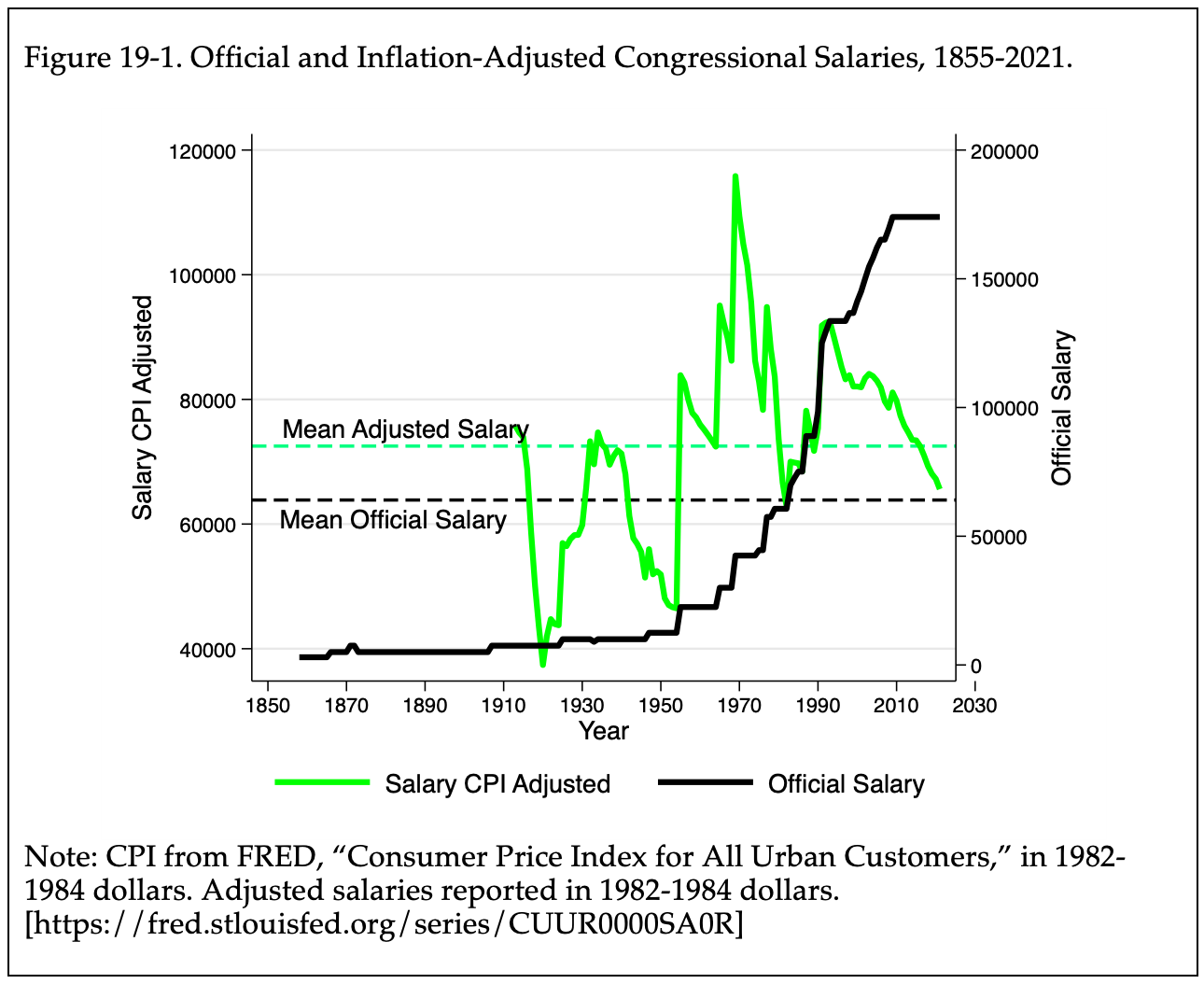

In 2019, when House party and appropriations leaders appeared to be making room in the budget for a salary increase for members of Congress, several Democrats facing difficult reelection efforts protested. The leadership backed off. In fact, congressional pay has not increased since 2009, when the salary was set at $174,000, with top leaders getting extra pay (Figure 19-1). The speaker of the House has a salary of $223,500; the president pro tempore of the Senate and the majority and minority leaders in the House and Senate receive salaries of $193,400.

Congress paid its members per diem until 1855, when it set a salary of $3,000 per year. The salary reached $10,000 in 1925. The salary has increased frequently since the 1950s, reaching $174,000 in 2009. The salary has stayed there due to congressional votes to turn down cost-of-living increases since then.

The real value of congressional salaries—that is, the base salary adjusted for inflation--has varied widely, as Figure 19-1 shows. Inflation cut into the value of congressional salaries in the 1970s and 1980s. In the late 1980s, Congress approved sizable increases to catch up, but since then the inflation-adjusted value of legislators’ salaries has been falling. In the last few Congresses, the inflation-adjusted salary has fallen below the average for the period since 1913 for which price index estimates are available.

The salaries of legislators always have been a sensitive political subject. Legislators want compensation commensurate with their professional duties, but many people in the public and among those seeking to unseat incumbents are eager to be critical of pay raises. Legislators, as members of an institution that often fails to live up to public expectations and who vote on their own pay raises, have always found this and associated issues (retirement and health insurance plans, honoraria, per diem) among the hottest of political hot potatoes.

In an effort to minimize the political costs of pay increases, Congress established a quadrennial salary commission in 1967 and first used it the next year. The idea was that an independent commission, activated every four years, would recommend pay hikes. On three occasions, the commission’s recommendations led to salary increases; on three other occasions, Congress did not approve commission recommendations. The commission was replaced in 1989, but its successor never met.

Overlapping the commission experience, Congress provided for automatic pay increases along with the increases for federal employees in a 1975 law. The hope was that an automated process would allow the pay hikes to take place without congressional votes. It did not work, at least not for long. During the 1990s and into the new century, Congress let the automatic increases go into effect for a majority of years, but Congress has rejected salary increases in every year since 2009. The Great Recession made salary increases politically unacceptable and avoiding blame for raising pay has been the dominant motivation since then.

The issue remains red hot whenever it is raised. In 2019, the legislative appropriations bill was pulled from the House floor when leaders discovered that passing it without a pay-freeze provision was impossible. In July 2021, the House passed a legislative branch appropriations bill that directed that a study of salaries for comparable professions in the private sector be conducted by CRS or another appropriate agency as a step to allowing a pay hike to go into effect or to justify the adoption of a new salary-setting policy. Nevertheless, pay freezes were enacted again in 2022 and 2023.

However, in 2023, a crack appeared in congressional opposition to pay hikes when the House Administration Committee, under its authority to set accounting practices for the House, unanimously approved a new policy that did not require legislation. Members of the House may get reimbursed for hotel stays, rent (but not mortgage payments), and utilities and insurances for property rented or owned in D.C.—but only for days on which the House is in session or committee meetings. Members living within 50 miles of D.C. may not receive lodging-related reimbursement. The advocates of the policy observed that members must spend considerable time in Washington, D.C., and their home districts, usually requiring that legislators maintain two residences and leading many members to sleep in their Capitol Hill offices. Legislators’ reimbursements are capped at levels that apply to other federal workers. Reimbursements are paid out of members’ office accounts and so do not increase spending.

In addition, at the time of this writing in September 2023, prominent House Republicans were advocating allowing an automatic cost-of-living increase to go into effect in early 2024. This would happened if no pay freeze is placed in the fiscal year 2024 legislative appropriations bill. At a time when most House Republicans were pushing for real cuts in domestic spending, it seems unlikely that the pay raise will survive year-end negotiations over spending bills. The Senate has not taken any similar action.