As incredible as it seems now, the late 1970s brought concerns about extreme decentralization in House policy making, so extreme that there was serious concern about the ability of “subcommittee government” in the House to enact complex but integrated legislation. The subcommittee government phrase was a twist on the term “committee government” used to describe House decision making in the mid-20th century.

Things have changed. Today, subcommittee chairs have smaller staffs, small budgets, and much less independence in setting subcommittee agendas. Policy making has moved into the hands of full committee chairs who often find their involvement directed by party leaders.

This did not happen overnight so it requires a little narrative about some important transitions.

The number of House and Senate standing committees was halved by the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, leaving both houses with committees that had larger policy jurisdictions and memberships and guaranteed funding for staff. This move created the modern committee system. Reforms since 1946 have made modest changes in the number of standing committees, juggled policy jurisdictions to account for new issues, and renamed many committees to reflect new issues and partisan priorities.

In response to the changes implemented with the 1946 act, some committees created subcommittees for the first time and others increased the number of subcommittees (Figure 22-1). At first, many committees adopted four or five subcommittees, often with responsibilities that reflected the jurisdictions of the previous full committees that were now folded into one committee. Over the next two decades, the number of subcommittees grew incrementally. New issues and members seeking a chairmanship provided motivation for the growth. Factional differences between full committee chairs and other committee members sometimes provided impetus to create a new subcommittee and at other times provided resistance.

Committee experiences were quite varied. There were no chamber or party rules that regulated the number of subcommittees a committee could create or the degree of independence that subcommittee chairs had in using a subcommittee to promote legislation through hearings and markups. Full committee chairs could create subcommittees and appointment their chairs and members. House Appropriations had 13 subcommittees, one for each appropriations bill; House Ways and Means, after Wilbur Mills (D-AR) became chair in 1959, had no subcommittees. Most committees had four or five subcommittees, some with little freedom to act and some with a great deal of independence.

House Democrats, as demanded by party liberals, adopted a party rule in 1974 that required all committees to create subcommittees. The rule, usually dubbed the Subcommittee Bill of Rights, reflected a desire to limit the power of full committee chairs, many of whom were conservatives whose control over committee affairs was resented by liberals. The party rule required every committee other than Rules to have four subcommittees, took the power to select subcommittee chairs away from full committee chairs, and guaranteed subcommittees referral of legislation and staff. This imposed substantial uniformity across committees in their use of subcommittees.

An immediate result of the Democrats’ 1974 rules was an increase in the number of House subcommittees. However, with some of the same concerns in the Senate, Democrats on several committees in that chamber demanded and received the creation of more subcommittees—and subcommittee chairmanships. Since the 1970s, about half of House majority party members and over 90 percent of Senate majority party members have chaired a full committee or subcommittee. In the Senate, most majority party members have chaired more than one committee or subcommittee.

After the rapid expansion of the number of subcommittees in the 1970s, House Democrats adopted rules to limit the number of subcommittees that a committee could have, which had a modest effect. The basic structure of the system—committees with a sizable number of active subcommittees—remained. A consequence of subcommittee expansion, the House Democrats’ rules, and Senate practice was an increase in the number of legislators who, as subcommittee chairs, could call hearings, hold markups, and serve as bill managers on the floor.

The Subcommittee Bill of Rights had a democratizing effect, a decentralizing effect, that benefited many members of the majority party in the 1970s, 1980s, and into the 1990s. While the concerns about extreme decentralization faded as party leaders asserted more influence over policy making during this period, the ability to gain a subcommittee chairmanship with some autonomy to pursue an agenda after just a few years of service in the House or often immediately in the Senate was enjoyed by a whole generation of majority party legislators.

All of that changed after the 1994 elections brought in new Republican majorities in both houses. House Republicans, of course, were not operating under the Democrats’ party rules governing subcommittees. Republicans in both houses slashed committee budgets and staff, returned control over subcommittees to full committee chairs, and the number of subcommittees, more radically in the House.

The number of subcommittees has not changed much since the 1990s. A few subcommittees were added in Congresses in which the Democrats were in the majority, but tight budget constraints have kept a lid on creating many. The result is that the House and Senate have been operating with subcommittees that number about the same as the number in the late 1950s.

The combination of a shrinkage in the number of subcommittees, less independence for subcommittee chairs, party domination of policy making on major issues, and legislative stalemate has had predictable effects on the volume of committee activity and the legislative productivity of subcommittee chairs.

The volume of committee activity—here measured as the number of full committee and subcommittee meetings combined—is shown in Figure 22-2. Since the 1990s, committee activity has been at a level lower than observed at any time since the late 1940s. The size of the active legislative agenda, particularly under Republican majorities, and legislative gridlock have reduced both the incentives to hold hearings and the need to conduct committee markups. But the inability of subcommittee chairs to freely schedule hearings and markup legislation since the 1990s, which represents a distinct “regime” in congressional policy-making processes, has had a major effect. This regime change in the 1990s had a much greater effect in the House than the Senate, due to the strong and more uniform empowerment of subcommittees that took place in the House in the mid-1970s.

The current party-oriented regime of House policy making places subcommittee chairs in a very different place in the policy-making process than the 1970s-1990s era. To illustrate this, I used a “legislative production” score, usually labelled in a misleading way as a “legislative effectiveness” score. The “legislative production” score is based on how far through the process—committee action, floor action, approval in other house, enactment—for the bills sponsored by a legislator.[1] This is a narrow measure. It reflects the outcome for bills each legislator formally authored. It does not account for each legislator’s contributions to the text of a bill, which might have taken the form of influencing a committee chair’s mark (initial draft), amendments adopted in committee or on the floor, or post-passage changes that are incorporated in conference or in some other way. It also does not account for bills folded into other bills, the multiple titles and sections of omnibus appropriations bills, or committee recommendations placed in reconciliation bills. In the narrow sense of identifying legislators whose names are formally attached to legislation, the scores reflect changes in the policy-making process typical in both houses.

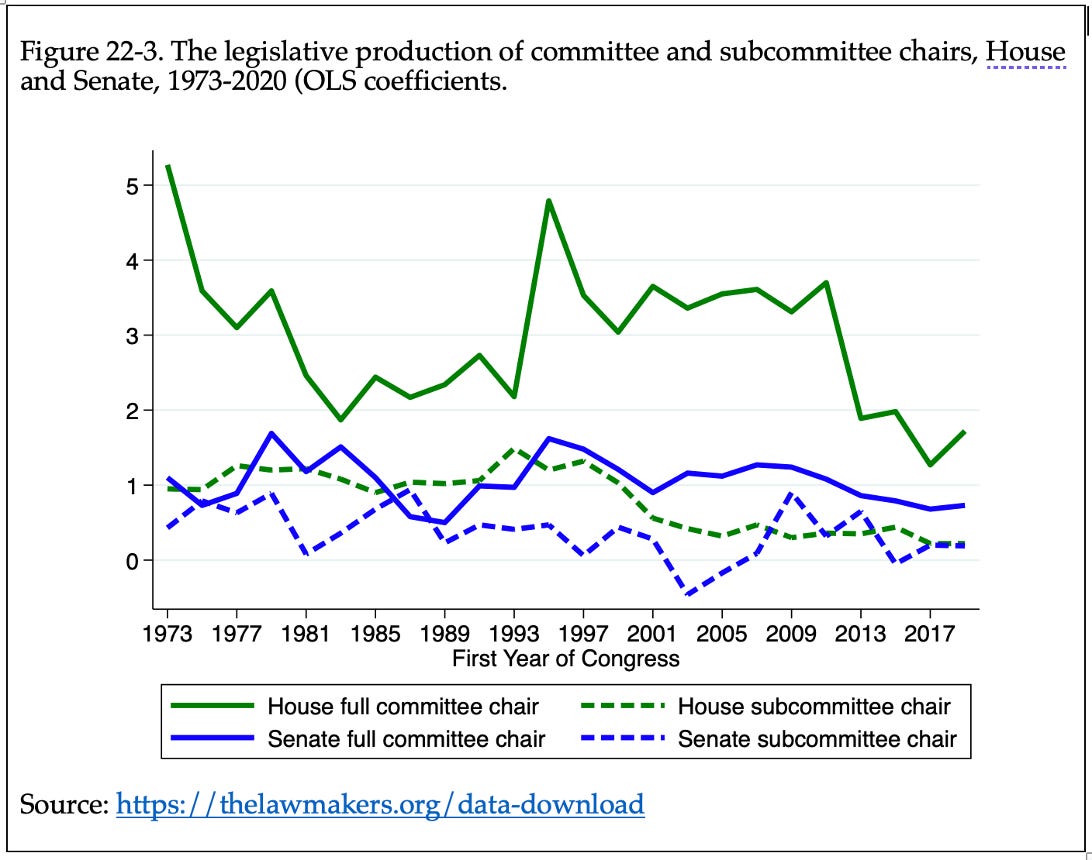

For each Congress since 1973, I have estimated the effect of being a full committee chair and subcommittee chair on their legislative production score.[2] The results for House and Senate full committee chairs and subcommittee chairs are shown in Figure 22-3, in which the vertical axis is the statistical estimate of the importance of being a chair or subcommittee chair. Higher values mean higher average production scores.

In the House, the arrival of a Republican majority in 1995 unraveled two decades of a Democratic regime in which subcommittee chairs had a hand in shepherding legislation through the process. After full committee chairs took the reins of their committees in the party-oriented regime instituted by Gingrich and the Republicans, the net effect of being a full committee chair on successful authorship increased by more than 50 percent and soon fell about 50 percent for subcommittee chairs. The regime survived the return of Democratic majorities in 2007. In recent Congresses, partisanship and gridlock generated less legislative productivity overall, so much so that even the legislative production of full committee chairs fell measurably. House subcommittee chairs have been less productive than their counterparts in the 1950s.

The Senate has not experienced changes in the use of subcommittees nearly as dramatic as those of the House. Switches in party control have not produced changes in rules and practice in the Senate that are nearly as great or lasting as those in the House. In fact, since the 1970s, Senate committees have greater variation in their use of subcommittees than House committees.

The balance of full committee and subcommittee chair authorship must be placed in a larger context of a decline of committee activity overall since the 1990s, as Figure 22-2 illustrates. As committee activity shrunk to remarkably low levels in the most recent Congresses, the productivity of both full committee and subcommittee chairs has dropped below the levels experienced in the previous half century. Committee agendas have shriveled, leaving both full committee and subcommittee chairs with their names on far fewer bills than we have experienced for many decades.

At the same time, as Notes 2 and 20 detail, more key policy decisions are made outside of the formal processes of committee or subcommittee hearings, markups, and votes to report legislation. On a quite ad hoc basis, senior committee leaders, almost entirely on the majority party side, are brought into negotiations immediately before floor action or in post-passage negotiations with the other chamber to determine key features of important measures. A few senior majority party leaders of committees remain involved but often without meaningful participation by the minority party or even rank-and-file committee members of the majority party.

____________________

[1] I use the “legislative effectiveness score” produced by Craig Volden and Alan Wiseman, available at https://thelawmakers.org/data-download [accessed May 15, 2021]. I consider the score to be a measure of “progression through the legislative process”—more a measure of legislative production than personal effectiveness, as it is often considered. Productivity is heavily influenced by the institutional setting, including the power allocated to committee and subcommittee leaders, the party leadership, and procedures for considering legislation on the floor.

[2] OLS estimates are calculated for the House and Senate separately. For each Congress, the estimated equation for productivity includes independent variables for being in the majority party, seniority, a full committee chair, and a subcommittee chair. Figure 2-2 reports the coefficients for being a full committee chair and for being a subcommittee chair, controlling for being in the majority party and seniority.