A colleague, Patrick Tucker, and I asked reexamined an old question about House and Senate campaigns: Do congressional campaigns make a difference?[1] The answer is not surprising, but it is important.

Political scientists seeking to generalize about the effects of campaigns on election outcomes have gone hot and cold and hot again on campaigns. The central question is whether certain political fundamentals—the electorate’s partisanship, incumbency, the state of the economy, presidential popularity—determine voters’ choices so completely that there are few voters left for the election campaigns to influence. The wobble we see in polling during campaigns may be due to the temporary effects of events that occur during campaigns and the vagaries of survey research.

The most notable study in support of campaign effects in presidential races was conducted by Hillygus and Jackman of the 2000 presidential contest.[2] The study was based on a panel—interviewing the same individuals at two or more times over the course of a campaign—which permits inferences about the effects of intervening events on views of the candidates. The central theme of the Hillygus-Jackman study is that voters vary in their responses to campaign events. The people most likely to change candidate preference were partisans who initially preferred the opposite-party candidate and independents, who were likely to have conflicting views of the two major party candidates. Also likely to “change,” at least in a narrow sense, were people who were initially undecided and made up their minds about the candidates during the campaign. Obviously, in a close contest, a campaign that crystallizes the support of partisans and generates support from independents and undecideds can influence the outcome.

We used a panel, too, but were motivated by a puzzle about where we might find the strongest “campaign effects.” Would campaign effects be strongest presidential, Senate, or House campaigns? The simple expectation is that the potential change in candidate evaluations is greater when more voters are exposed to information about the campaign and candidates. Thus, presidential races have greater potential campaign effects than Senate or House races, and Senate races generally have greater potential campaign effects than House races. Yet, potential campaign effects are limited by the presence of voters with strong dispositions about the candidates at the start of a campaign. It is reasonable to expect initial preferences to be most durable in contests that involve important offices and candidates who are well known at the start of a campaign season, the same contests in which campaign signals are sufficiently strong to expect sizable campaign effects. Thus, based on the strength of early candidate preferences, we expect the strongest campaign effects in House races, followed by Senate races and presidential races.

We used The American Panel Study (TAPS), which was a monthly online panel with a national probability sample, for the 2014 and 2016 election cycles. In both 2014 and 2016, TAPS panelists were asked questions about their local Senate and House candidates at two points in time. The first questions were asked in the month immediately following each respondents’ congressional primary. The dates of congressional primaries range from March to September so the battery of congressional candidate questions was presented to the corresponding panelists between April and October. Campaign season effects were measured as the change in responses about the candidates between the post-primary wave and the post-general election wave.

Don’t Knows

We asked two sets of questions that were asked about the candidates before and after the general election campaign. One set asked the panelist to indicate the position of each candidate on ten issues. The second set asked the panelist to indicate the ideological location of each candidate on a five-point scale. We are interested in the number of “don’t know” (DK) responses across the three types of races and between the beginning and end of the general election season.

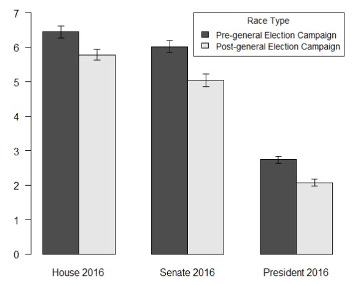

Figure 25-1 displays the average number of DKs for candidates’ positions on a 10-item issue battery and for candidates’ positions on a liberal-conservative scale. In the pre-general election campaign season, panelists exhibit the least familiarity with House candidates and the most familiarity with presidential candidates. In fact, the differences between congressional and presidential candidates is very large. For example, the average panelist could not identify the policy position of roughly 6.5 of a given House candidate’s 10 policy positions, while the same figure only registered a 2.7 for a presidential candidate. Similarly, in both 2014 and 2016, the average panelist could not identify a given House candidate on the ideological scale between 46 and 49 percent of the time. For the presidential candidate, only 16 percent of panelists were unable to identify where Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton were on the ideological scale.

The change observed in panelist provided information over the campaign season presents a similar story. Panelists showed a significant reduction in the number of DK responses in the congressional races. With respect to the issue battery, the average number of DKs decreased by roughly 1 issue for House and Senate races. The decrease for the ideological scale was also a significant drop of 11 to 14 percent in those races surveyed. Although there is significant improvement in the issue battery for the presidential race, we found that panelists had hardly any improvement in their ability to locate Trump and Clinton by the time of the general election. These results indicate a somewhat greater campaign effect in the congressional campaigns than in the presidential campaigns.

Making Up Your Mind/Changing Preferences

The number of people changing their candidate preferences showed a pattern consistent with the view that House campaigns have greater effects, on average, than Senate campaigns and that presidential campaigns have the smallest effects. I encourage you to look at the paper (cited in footnote 1). Here is a quick summary:

The number of undecideds increases as we move from presidential to Senate to House contests. That is, initial conditions vary systematically across the three types of races, as expected.

In all three kinds of races, and overwhelmingly, partisans stay with their party’s candidates through a campaign. Nevertheless, partisans are more likely to switch to the candidate of the other party in House and Senate races (3-10 percent) than in the presidential race (1-2 percent).

House and Senate races exhibit much more change during the campaign season than the presidential race. This holds for change from one candidate to another and for change from undecided to a candidate.

The 2016 presidential campaign effect, like the 2000 effect for Hillygus and Jackman, is primarily changing undecideds to one of the two major party candidates. In 2016, this campaign effect helped Trump disproportionately.

The initial puzzle—does initial familiarity limit campaign effects or do differences in the attention and contestedness of races intensify campaign effects—is solved in favor of initial conditions when comparing House, Senate, and presidential contests. Moreover, among House and Senate contests, we found no systematic campaign effects even in more contested races.

One more piece of evidence shows the large differences in campaign effects across the three levels of campaigns. For each panelist, we determined how accurately he or she identified the policy position of the Democratic and Republican candidates. We did this before and after the campaign so that we could determine whether the intervening months yielded greater improvement in knowledge or one candidate or the other. In Figure 25-2, the horizontal axis shows whether knowledge of the Democratic candidate improved more (positive) or the Republican candidate improved more (negative).

The change in knowledge advantage should be related to which candidate won the panelist’s vote. It is, but only for undecided voters and far more for undecided voters in House races than in Senate races and much more so than in presidential races. For voters who are initially undecided (green dots), the probability of voting for the Democrat rises as we move from a Republican gain in familiarity to a Democratic gain in familiarity for every kind of race. However, the effect is much greater in House contests, where knowledge of the candidates tends to start low, than in the presidential contest. Having a clear candidate preference at the start of the campaign (blue and red dots) tends to produce no or little change in probability of voting for the Democrat even for voters whose knowledge of the candidates became more lopsided.

A Few Takeaways

Some reasonable conclusions about the three levels of federal election campaigns:

Some voters learn candidates’ policy positions over the course of congressional and presidential campaigns;

Voters show the least uncertainty about the presidential candidates at the start of the campaign and the most uncertainty in House contests;

Voters evaluations of the candidates change the most in House contests and the least in the presidential contest;

Relative knowledge of the candidates has the greatest effect in House races and least effect in the presidential contest; and

Voters who are most likely to systematically change their support during a general election campaign move in a manner that is consistent with their beliefs about the president and their partisan identification. Mismatched party identifiers are likely to “return home” to their party.

Overall, initial preferences are very stable among those voters who express preferences at the beginning of the general election campaign. Nonetheless, these stable preferences only demonstrate a portion of the campaign narrative.

One last point: These findings are certainly time bound. This is an era of strong partisanship and nationalized congressional elections (Note 6). The differences in campaign we see between House, Senate, and presidential campaigns in the 2014 and 2016 election cycles almost certainly were even greater a generation ago. What candidates do when in office and in their campaigns surely had a greater effect on election outcomes in a previous era in which party allegiances did not run so wide and deep.

[1]Patrick D. Tucker and Steven S. Smith, “Changes in Candidate Evaluations over the Campaign Season: A Comparison of House, Senate, and Presidential Races,” Political Behavior (March 29, 2020). More on Patrick Tucker here.

[2] D. Sunshine Hillygus and Simon Jackman, “Voter Decision Making in Election 2000: Campaign Effects, Partisan Activation, and the Clinton Legacy.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (2003): 583-96.