Note 3. The Search for Causes

Partisan Polarization and Intensifying Partisanship

The terminology of polarization and partisanship is messy and often confusing, made worse by very casual use of the terms in popular commentary.

By polarization, political scientists usually mean “the increasing support for extreme political views relative to the support for centrist or moderate views.”[1] Partisan polarization is a polarized distribution in which legislators (or supporters) of the two parties occupy opposite ends. In Note 1, I provided some evidence of partisan polarization.

Partisanship, in contrast, is a bias in favor of one party and against the other party, whatever the political views of the party. In Congress, we usually refer to partisanship when we observe that one party or the other is acting to enhance its own political position at the expense of the other party for reasons that have little immediate connection of policy objectives. We usually have in mind public relations and electioneering, rather than immediate legislative objectives, as the outlets for partisanship. It is associated with team play.

Partisan polarization and partisanship feed on each other. Partisan polarization reduces cross-party activity and breeds a we vs. them mentality; partisan interests can shape legislative strategies. Distinguishing the effects of partisan polarization and partisanship in seeking to explain the behavior of legislators and their party leaders is not easy and often impossible.

Yet, analysts seeking to explain partisan polarization and partisanship usually treat one or the other without drawing an explicit connection between them. Partisan polarization, for example, is properly associated with the replacement of southern Democrats, mostly conservatives, with conservative Republicans over the last three decades of the 20th century. However, the election of conservative Republicans from the South made the Republicans more competitive in their effort to gain and maintain majority control of the House and Senate, which encouraged both parties to give higher priority to electoral considerations and “message politics” in their everyday activity on Capitol Hill.[2] In turn, “legislating as electioneering” generated resentments and distrust, making bipartisan efforts less likely and further fueling partisanship.

The spiral of partisan polarization and partisanship also is reflected in the forces American politics that generate it. The intensifying partisan polarization and partisanship is not the product of any one development. A broad set of forces interact to generate the long-term pattern we have witnessed. To be sure, there are important sequences of events that help us sort cause and effect and there are developments with demonstrably minor consequences. Still, it is useful to provide a general framework for understanding how several features of American political life influence, and are influenced by, the partisan polarization and partisan strategies in Congress.

Figure 3-1 provides a way to visualize some of the most important relationships. Each set of actors is diverse; each arrow has a story and often several. For example, the realignment of the southern electorate stimulated greater partisan polarization in Congress (arrow a), while polarized parties in Congress encouraged voters to sort themselves into two camps—one Democratic and liberal, one Republican and conservative (arrow b). Legislators appeal to donors, often by grabbing headlines with partisan parliamentary moves or ideologically-charged rhetoric (arrow c); more extreme activists and campaign donors create incentives for more extreme or less compromising behavior by legislators (arrow d).

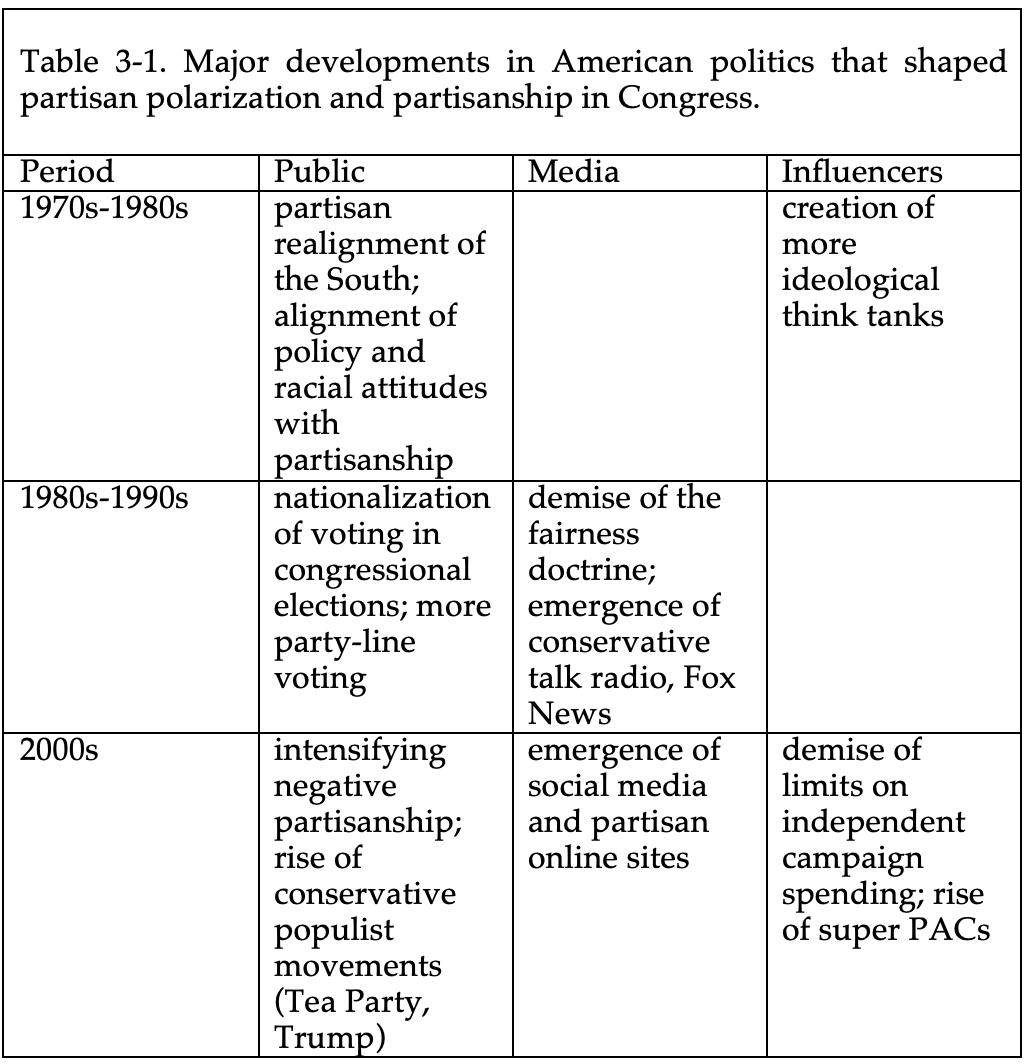

This is a big subject so I cannot detail the forces in American politics that are influencing the partisan polarization and partisanship we have witnessed in Congress, but I can list a handful of the most important forces, as I do in Table 3-1. My purpose is not to exclude some events, but rather to draw attention to the web of factors that influence, and are influenced by, developments in Congress.

McCarty’s review of the evidence led to this fair summary:

The polarization of the American political parties is a complex phenomenon with many plausible causes and is influenced by an even larger set of contributing factors. For ultimate causes, it seems logical to focus on those economic, political, and social changes that appear roughly contemporaneously with the emergence of party polarization in the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, strong cases can be made for a wide variety of causes ranging from the Southern Realignment to increasing economic inequality and racial/ethnic diversity to the reemergence of strong party competition for the control of the federal government. But whatever the sparks, certain accelerants have played important roles. Polarized politics produces a vicious cycle when it drives moderates from public life or encounters new media technologies that can serve to reinforce ideological messaging and partisanship.[2]

This state of affairs should persuade you that there is no simple solution to partisan polarization or intense partisanship. Nevertheless, reform proposals have multiplied. Every element and arrow in Figure 3-1 has drawn commentary about the need for dampening extremism and partisanship and, in most cases, have included proposals to alter the rules of game. Some of the proposals, such as ranked-choice voting, top-two primaries, and some campaign reform proposals, are intended to take nominations out of the hands of more extreme activists and primary voters and to elect more moderates to Congress. Others are intended to change the balance between moderate and extreme political forces and between factual and false information. Some seek to modify congressional parliamentary procedure. And yet others seek to alter how the House, Senate, and the president represent the nation.

The proposals include:

Electorate and elections: Restoration of civic values and civic education; ranked-choice voting; top-two primaries; nonpartisan districting; automatic voter registration; more convenient or mandatory voting.

Media: Reinstitution of the fairness doctrine; regulation of social media and online disinformation.

Influencers: campaign finance reform; lobbying reform; strengthen (or weaken) party control of nominations and campaigns.

Congress and the president: filibuster and other procedural reforms; expand the size of the House; proportional representation of parties in the House; alter state representation in the Senate; abolish the Senate; abolish the electoral college system (direct popular election).

A case can be made that the information age has fundamentally and permanently altered the political landscape. The geographic variation in the electoral coalitions that once supported the two parties has evaporated as activists and the media reach so easily across cities, states, and regions. If so, some of the localism that created some diversity of interests within each party and occasionally generated influential minor parties has weakened. Of course, it is frequently observed that groups with narrow interests can more easily organize on a national basis and might form new parties, but our experience with the Tea Party and conservative populists in the last two decades suggests that a major party will exploit these developments to expand its base rather than reject extremist views altogether. The forces favoring partisan polarization now run very deep in American politics and are unlikely to change much in the next decade.

[1] Nolan McCarty, Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2019), 2.

[2] Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

[3] McCarty, op. cit., pp. 99-100.