Many observers have bemoaned the decline in the in the number of congressional staff members. Congress eliminated the Office of Technology Assessment in 1995, cut back on the number of policy evaluators in the Government Accountability Office, froze the size of the Congressional Research Service, and forced cuts in personal and committee staffs. Some commentators have called it a “brain drain,” complaining that Congress has limited the ability of committees to conduct oversight of the executive branch and undercut the ability of members to engage in creative legislating. Some, including me, have noted the remarkable increase in the number of party and leadership staff, which reflects the shift in legislative initiative from committees to parties and the rise of large party campaign and public relations staffs.

I have addressed some of these issues in other Notes, but it pays to dig a little deeper into the numbers and their interpretation.

The Numbers

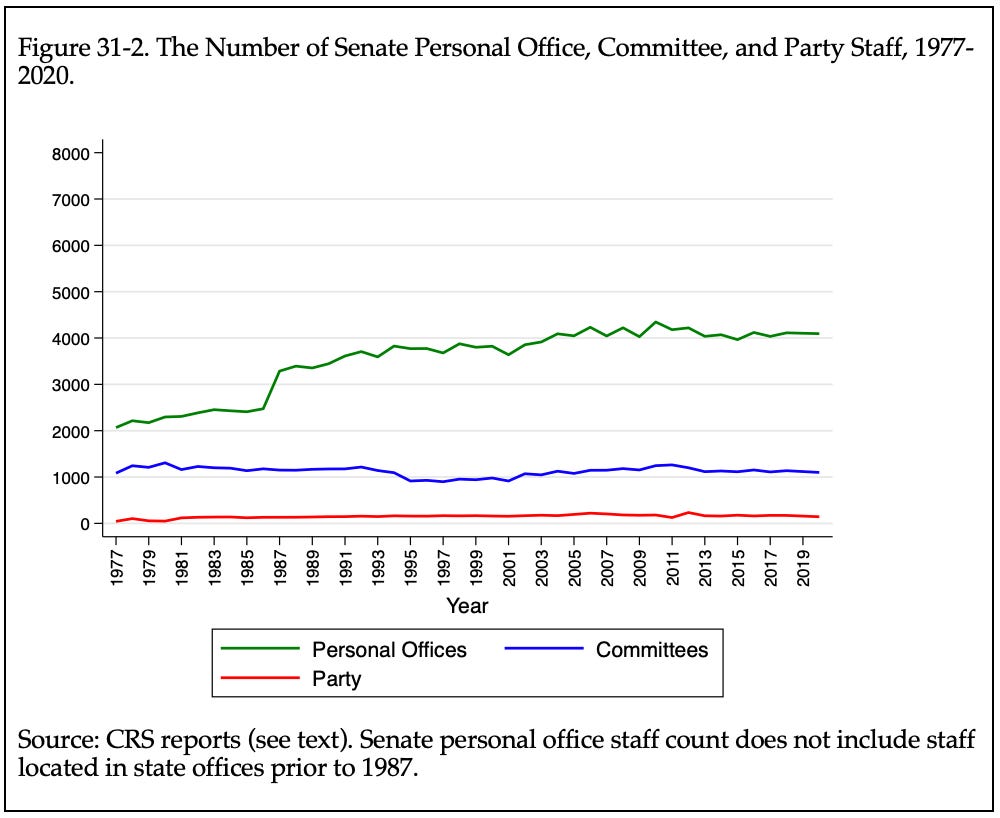

The number of staff in three major categories are shown in Figures 31-1 and 31-2. This count is borrowed from CRS reports, which, at the time of this writing, provide counts through 2020 for the Senate and 2016 for the House.[1] The counts are based on House and Senate telephone directories. The method leads to an undercount of staff. For example, the Senate directory did not include staff placed in state offices until 1987. Other counts rely on other sources such as clerk reports, the old Congressional Staff Directory, or the more recent LegisStorm and CQ Knowledgis compilations. The count in the figure does not include staff in the office of House and Senate officers, a few of whom consider themselves to be working for the majority party.

There are several features of the figures and associated developments worth noting:

House committee staff took a dive after the Republicans took over the House and Senate in 1995. The break was particularly sharp in the House, where Speaker Newt Gingrich wanted to cut back on subcommittees and their staff (Note 22) and even asserted veto power over the hiring of senior committee staff. House committees have not returned to the same level of staffing.

A far more modest cut occurred in Senate committee staff, which moved back to pre-1995 numbers within a decade. Nevertheless, the overall number of Senate committee staff remains somewhat smaller than the number for the House.

In the House, personal staff sizes have remained within a fairly narrow range since the mid-1970s, when the House adopted a rule, which remains in place, of limited House offices to 18 full-time and 4 part-time employees. In the House, district office staffs were pared back a little in the last decade as budgets have tightened, but, district staffs were only about one-third of personal office staff in the early 1980s and grew to about half in the 2010s (see Footnote 1).

In the Senate, personal staffs have grown, but nearly all of the growth has been in state offices. In fact, between 1987 and 2020, the number of personal staff located in their Capitol Hill offices did not increase; the number of staff located in state offices nearly doubled (see Footnote 1).

Adjusted for inflation, flat funding for congressional offices during the 2010s produced a substantial reduction in real income for staff.

Somewhat difficult to see in these figures is the growth in staff hired by party leaders and party committees. I show party staff counts in Figure 31-3. As committee staffs were cut and, in the case of the Senate, only slowly recovered, the staffs of top party leaders and party committees grew. In both houses, party staffs quadrupled in size.

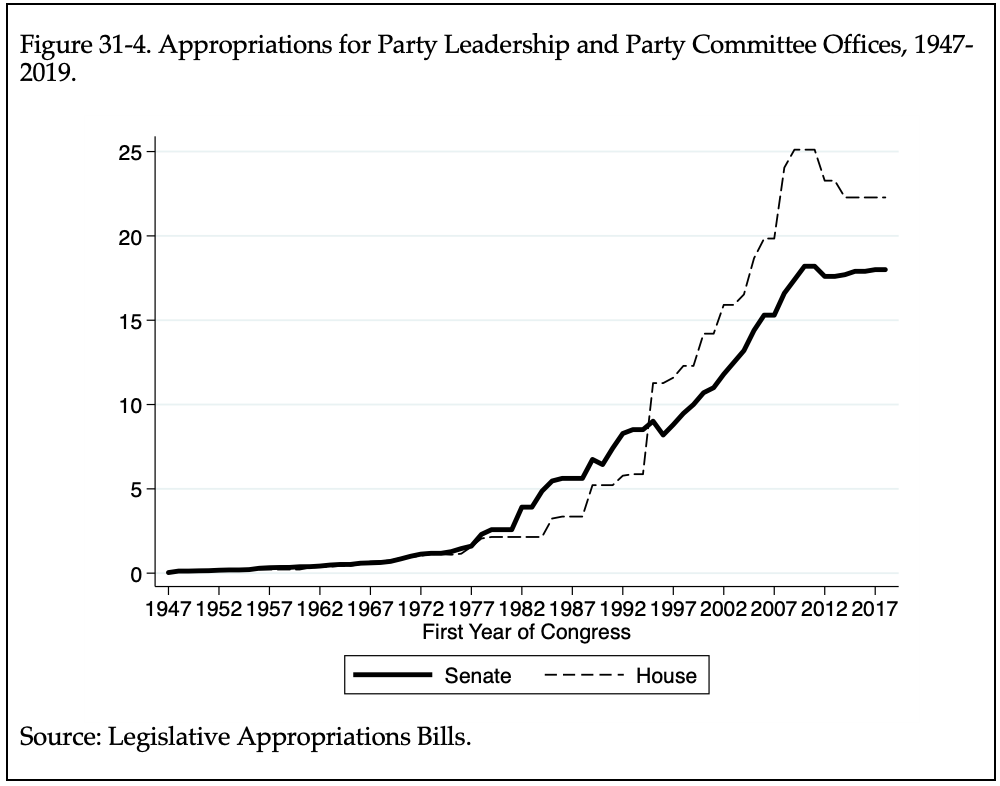

The Senate party staff count is quite ragged in the last decade. Not having inspected the Senate telephone directories myself, I cannot account for this, but it surely has something to do with the identification of staff in the telephone directory. What I can say is that funding for Senate party staff has climbed steadily until recently. I show this in Figure 31-4. In both houses, budget constraints under the 10-year spending caps of the Budget Control Act of 2011 kept spending on party staffs flat over the last decade. They are now lifted. Until then, the level of support for staff housed in the offices of party leaders and party committees climbed quickly in the last half century, in sharp contrast to the virtually flat spending on committee staffs.

The congressional support agencies—the Congressional Research Service, Congressional Budget Office, General Accountability Office (formerly General Accounting Office), and the defunct Office of Technology Assessment—have been important sources of expertise to committees, individual legislators, and leaders. I do not have up-to-date numbers for staffing in these agencies, but funding and staff levels for these agencies has been flat or falling for years (Figure 31-5):

CRS, which was expanded after its transformation from the Legislative Reference Service in Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, has experienced a shrinking staff since the Republicans took majorities in 1995.

CBO, which was created by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, has added a few staff to manage its burden of providing budget and economic analyses to Congress.

OTA, which opened in 1974 to provide expertise to Congress on scientific and technological matters, was abolished by the Republicans in 1995 and has not been recreated.

Staff Salaries

Staff salaries, not surprisingly, have remained flat. Until August 2021, the maximum staff salary has been capped at the level of a member’s salary, $174,000, which has not been increased since 2009. Moreover, committee and personal office budgets have remained flat, too, keeping staff incomes in place while the cost of living in DC increased by nearly 10 percent.

2021 is bringing some changes. The House passed the legislative branch appropriations bill with a large increase (about 22 percent) for committee, personal, and leadership office staff. At the time of this writing, the Senate has not acted on its version, which normally would include the parallel funding for Senate offices. In the meantime, Speaker Nancy Pelosi ordered an increase in the maximum salary allowed for a House staffer—$199,300—which, of course, is larger than the salary of a member of the House. Until the budgets are increased, not many staffers will see that salary. Partisan divisions over spending do not insure that the House moves on staff funding will make it into law.

How is Staff Used?

The aggregate numbers hint at important changes in the use of staff. The increase in the number of staff in senators’ offices and party offices, the flattening of committee staffs, and cutbacks in support agencies may reflect a shift in emphasis from policy to constituency service and public relations. I think it does. In part, this represents a deliberate decision by congressional Republicans to limit policy innovation. It also is the by-product of flat budgets for the legislative branch that have squeezed funding for committees and support agencies. Overall, Congress’s dependence on the executive branch, organized interests, and others for information and advice has increased.

I do not have a count of jobs by title within party offices to show, but it is obvious that much of the expansion of staffs controlled by party leaders has been devoted communications, social media, and outreach. The balance between legislating and winning elections has shifted more strongly in favor of the latter. In the Senate, Democrats created separate party committees on communications and outreach in 1995 and then created “war room” to manage party messaging in 2005, both of which increases in staff and technical capacity. Republicans created a sizable communications staff under their floor leader’s control in 2007. Much happened in the party offices of both houses to enhance their capacity to wage public relations battles.

The more complete picture of leadership and party staffs must account for the enlarged policy staffs within leaders’ offices. Leaders and their staff call on committee staffs to work with them in writing legislation. As leaders have taken the initiative to guide legislating on the most important issues, they collaborate with committee leaders and staff to generate the text of bills.

More hidden from view has been a significant deemphasis in policy making in personal office staffs. A careful study of job titles held within House and Senate personal offices showed that the proportion of personal staff dedicated to legislative roles, as opposed to constituent service, communications, and administrative roles, has declined in the last decade. Low pay and long hours also generate considerable turnover: The median staff member stays just a little over three years and is 30-35 years old, and often sees the job only as a stepping stone to a private sector or lobbying job. There are long-serving staff in the most senior positions on party and committee staffs, but staffers dedicated to policy making personal offices are fewer and more poorly paid than they were two decades ago. [2]

Staff Pay

Until just recently, congressional staff salaries have been capped at the level of legislators salaries—$174,000 per year. Like members’ salaries, this cap has remained flat since 2009 while the cost of living in DC has increased at least eight or nine percent, which, of course, affected all staff. At the same time, the average salary of a legislative assistant in a personal office dropped 20 percent since 2010.

Concern about staff salaries came to a head in the summer of 2021. Leading Democrats recommended a substantial boost in salary budgets for personal offices in the House. At this writing in August, 2021, it is too early to know whether the efforts of the House appropriators to increase personal office budgets will succeed.

Final Notes

Congress is not devoid of staff expertise, but the expertise under its direct control is more limited than it was in the early 1990s. House committee staff and the support agency staffs are collectively much smaller than was true in the early 1990s. The ability of Congress to recruit and retain top-flight staff has suffered as the number of posts have declined and salaries have slipped.

These developments have made Congress weaker relative to the executive branch and organized interests. It has fewer people motivated and qualified to generate and implement policy ideas. It has fewer staff who have acquired networks that stretch across the parties and branches of government and facilitate policy making. It has more staff who are looking for an outside job soon after arriving.

The capacity of the individual legislators to contribute to policy making is lower. Subcommittee and personal staff assistance are now much more modest than in the early 1990s. Policy making has always involved collaboration with executive officials, lobbyists, and other outsiders, but independent, creative, entrepreneurial policy innovators are harder to find than a quarter century ago. Party-dominated policy making has played a role, but the legislative capacity of individual legislators has suffered.

In contrast, party leaders have far greater capacity to lead policy making and public relations efforts than they did a generation ago. They are now capable of writing complex legislation and running parallel messaging efforts.

—————————

[1]https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R43947.html; https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R43946.html.

[2]Alexander C. Furnas and Timothy M. LaPira, “Congressional Brain Drain,” New America, September 8, 2020.