Note 34. Proxy Voting

Gone for Now

Proxy voting was initiated in the House in May 2020 in response to the pandemic. Republicans ended it when they took over as the majority party in 2023.

When social distancing became important in the spring of 2020, the House adopted a rule that allowed the speaker to institute a 45-day period, renewable, during which a member could designate another member to vote for him or her. The speaker renewed the order through the remainder of 2020 and again throughout 2021 and 2022. By the end of 2022, proxies had been designated well over 6,000 times. The legislators’ floor votes cast by proxy constitute about 10 percent of all roll-call votes—nearly 40,000 times during the 117th Congress (2021-2022). On many votes, important and not so important, dozens of members’ votes have been cast by proxy—in October 2021, 161 members, over a third of the House, voted by proxy on the federal debt limit.

The proxy voting process is controversial but not well understood by outsiders. It bears attention as the House has acquired nearly two-and-a-half years of experience with it and considers rules to govern floor voting in the future.

The Proxy Voting Rule and Regulations

In May 2020, just a few months into the pandemic, the House considered how to meet the demand of health experts to mask and observe social distancing practices and yet to maintain the House’s role as a representative lawmaking body. Allowing remote voting by electronic device was given some consideration but readily rejected. A secure means for doing so was not in place. Virtual participation in committee meetings and hearings was more feasible and entailed few risks, but casting votes on floor roll-call votes was another matter. After considerable discussion, the majority Democrats proposed proxy voting—allowing a member’s vote to be cast on his or her behalf by another member. Their proposal was opposed by all Republicans, but a resolution to allow proxy voting was approved on a party-line vote.

The House had an explicit ban on proxy voting since 1995, when Republicans included the provision in their rules package. Neither committee nor floor proxy voting was permitted previously, although a few exceptions for committee voting had been approved in the past. The 1995 rule was amended by the 2020 resolution to create a procedure to temporarily approve of proxy voting on the floor and in committee.

The 2020 proxy voting rule, adopted by a party-line 217-189 vote, empowers the speaker of the House, in consultation with the minority leader, to announce a period of up to 45 days in which proxy voting is allowed on the floor and in committees. The speaker may extend the period for an additional 45 days if she “receives further notification from the sergeant-at-arms, in consultation with the attending physician, that the public health emergency due to a novel coronavirus remains in effect.”

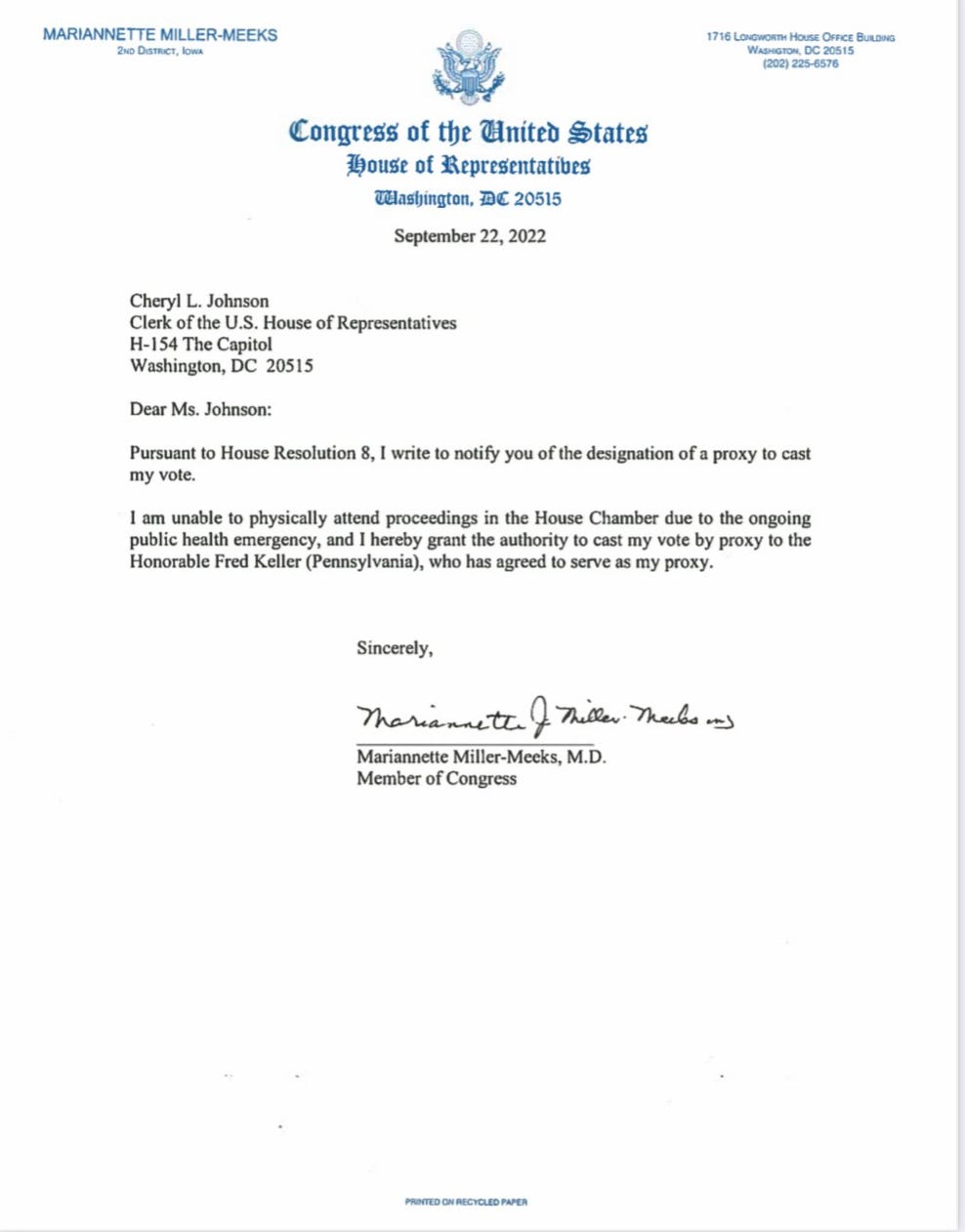

The rule specifies how a proxy is designated and how a proxy vote is cast. Absent members must send the House clerk a signed letter that specifies which member may cast their votes. The letter must include specific instructions from absent members to their physically present colleagues about how to vote their proxy. The rule limits to ten the total number of proxies that a physically present member can cast at one time. Members who are physically present are required to announce proxies before voting, a step that requires being recognized and reading a statement about the absent member and his or her vote to be cast.

The chair of the Rules Committee was authorized to issue additional regulations to implement proxy voting, which he has done. The chair produced regulations that provide more detail, templates for proxy-givers and proxy-holders, and a set of “best practices” recommended for members. These documents are available here: Proxy voting rules and regulations.

The authors of the rule anticipated one dicey issue by including a provision that “any Member whose vote is cast or whose presence is recorded remotely under this section shall be counted for the purpose of establishing a quorum under the rules of the House.”

The proxy letters to the clerk are published online, as are the names of members casting votes by proxy. Follow this link to see the proxy letters: Proxy letters. Votes cast by proxy are listed by the clerk under each roll-call vote. Go here for the votes and then click the “view details” and “remote voting by proxy” links: Roll-call votes.

The 2020 resolution also directed the House Administration Committee to “study the feasibility of using technology to conduct remote voting in the House, and shall provide certification to the House upon a determination that operable and secure technology exists to conduct remote voting.” The committee held a hearing a couple months later but has not taken further action on the matter.

Arguments Against Proxy Voting

Republicans, led by Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), made several arguments in opposition to proxy voting. The most prominent argument was that proxy voting violates the Constitution’s quorum, assembly, and adjournment clauses. The quorum clause:

Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members, and a Majority of each shall constitute a Quorum to do Business; but a smaller Number may adjourn from day to day, and may be authorized to compel the Attendance of absent Members, in such Manner, and under such Penalties as each House may provide.

The assembly clause:

The Congress shall assemble at least once in every Year, and such Meeting shall be on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by Law appoint a different Day.

The adjournment clause:

Neither House, during the Session of Congress, shall, without the Consent of the other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other Place than that in which the two Houses shall be sitting.

These clauses, critics insist, imply that members must physically “assemble” at least once a year and must be physically present to form a quorum and to be counted as convening.

In 2021, McCarthy and most House Republicans took the issue to court. Their case was dismissed on the basis of the “speech and debate” clause, which provides that “for any Speech or Debate in either House, they [members] shall not be questioned in any other Place.” That may seem strange, but legal precedent treats the clause expansively by extending to all legislative acts, which certainly include the adoption of rules governing voting. This led both the district and appeals courts to rule against the Republicans. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case. As a result, the courts remained silent on the contested interpretation of the key clauses and did not go as far as to endorse a broad view of Article I, Section 5, which provides that “each house may determine the rules of its proceedings.”

Republicans offered other arguments against proxy voting. The criticisms included:

By missing floor debate, members do not learn from and contribute to floor debate and face-to-face deliberation.

By reducing face-to-face meetings, many occurring incidental to going to and from the House floor, the practice undermines opportunities for bipartisan collaboration.

The process enhances the power of party leaders who still make members aware of party positions on legislation.

By enhancing the power of party leaders, the majority party is stronger and the minority party is weaker.

By reducing deliberation and bipartisanship, the role of the House in policy making is weakened.

The process is easily abused as members routinely attest to being absent “due to the ongoing public health emergency” while in fact being absent for many other reasons.

Republicans promised to restore the ban on proxy voting if they won a House majority in the 2022 election.

Proxy Voting in Practice

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) renewed the proxy voting process through the 2020-2022 period. The easing of the pandemic did not persuade Pelosi to stop the practice; her official reason for doing so was simply that she received notice from the sergeant-at-arms that the health emergency continued. I can only speculate that the Republicans were right—Pelosi and the Democrats, with their small majority, wanted to continue the ease of getting good “turnout” for votes among Democrats on floor votes and to make it easy for members to be home to campaign.

The abuse of proxy voting for reasons having nothing to do with the pandemic has proven to be widespread. To be sure, scheduling conflicts due to attending constituency events, making official trips, being in the home district after a natural disaster, and pursuing other activities that are considered a part of a legislator’s job are eased by having the option to vote by proxy. Even illness, giving birth, and family emergencies might even seem to justify absence and taking advantage of proxy voting. But journalists and others have documented many cases of clearly unjustified uses of proxy voting. These include voting while on vacation and attending funddraisers, conferences organized by special interests, birthday parties, and other events. Tim Ryan (D-OH), who was running for the Senate in 2022, had cast 268 proxy votes by August 2022.

Ryan, however, is far from the worst abuser. In 2021, Democrats Frederica Wilson (FL), Bobby Rush (IL), and Al Lawson (FL) votes by proxy 438, 435, and 435 times, respectively, out of 438 roll-call votes. None had pandemic-related excuses for nearly always failing to vote in-person, according to media accounts. A total of eight members, all Democrats, missed more than 300 votes. In 2021, the 21 members to top the list of voting by proxy were Democrats.

Republican leaders’ objections to proxy voting did not wane as Pelosi kept renewing the process, but Republicans, whose refused to vote by proxy in 2020, began to vote by proxy in sizable numbers in 2021. By the end of 2021, about 9 out of ten House Democrats and over 6 of 10 of Republicans had voted by proxy at least once. That mix appeared to continue through 2022, for which we do not have final numbers at the time of this writing. In 2021, nearly 10 percent of all votes cast (members times votes), about 10 percent were cast by proxies—17,263 votes.

The Ripon Society, the moderate-to-conservative Republican group, tabulated proxy voting by member for 2021 over the 438 roll-call votes conducted that year.* Their tallies:

The mean number of proxy votes cast by Democrats and Republicans, respectively: 55.6 and 22.2 times.

101 members did not cast even one proxy votes that year—78 Republicans and 23 Democrats.

65 members, 57 Republicans and 9 Democrats, neither voted by proxy nor voted another member’s proxy in 2021.

The frequency of proxy voting did not slow in 2022 (which is not over at this writing in October)—and became more common as primary elections and general election campaigning approached. One result is that the number of members casting roll-call votes—in person or by proxy—reached a record average of 97.8 percent in 2022, despite the fact that campaigning kept many legislators away from the Capitol for much of the year.

The full distribution for 2021, shown in Figure 34-1, shows that most members appeared to observe the general intent of the proxy voting process—to enable members to be away from the House when ill, exposed to the virus, or dealing with family or travel issues associated with the pandemic. Missing two or three dozen votes seems expected. Beyond that, in the absence of a long-term personal or family illness due to the pandemic, is not well justified under to intended purposes of the proxy voting process. While Democrats exploited the process much more frequently than Republicans, on average, we should realize that the one or two dozen extreme abusers on the Democratic side pulled up the party mean.

Further evidence of the abuse of proxy voting was pulled together by Roll Call, the Capitol Hill newspaper. In its study, using votes in 2021 and the first nine months of 2022, an average of 41 proxy votes were cast on days that were neither the start of a work week (fly-in days) or the end of a work week (fly-out days), in contrast to 57 on fly-in days and 62 on fly-out days. Roll Call reporter Chris Cioffi observed one legislator preparing a handwritten proxy letter in person on the House floor, testifying that he was “physical unable” to be present because of the pandemic and then having subsequent votes cast by proxy.

A Final Thought

The quickly spreading COVID-19 virus in early 2020 forced the House to scramble to meet the health threat and exposed the lack of lasting ways to ensure the functioning of Congress. With the end of the health crisis, Republicans ended proxy voting in when they took over as the House majority in 2023. Democrats did not complain.

The three-year experience with proxy voting in the House left important issues unaddressed. In my view, the House (and Senate, I must add) must have an alternative to in-person voting that allows the legislative branch to operate in a national health emergency or other dire circumstances that prevent in-person participation at the Capitol. A national legislature that suddenly cannot make law is not consistent with the spirit of the Constitution or democratic government. In fact, remote voting should be a part of a larger effort, sorely needed, to account for a broader range of situations, including an attack on the Capitol, the need to select new leaders if top leaders were incapacitated, or even everyday situation when a member’s health circumstances make him or her temporarily unable to travel.

*https://riponsociety.org/2022/01/proxy-voting-in-the-house-in-2021/