Note 6. Party and Incumbency

The Nationalization of Congressional Elections and Partisan Polarization in Congress

The nature of congressional elections has changed in important ways over the last half century. These changes have influenced the strategies of congressional party leaders and how congressional parties approach the electoral process. In fact, we have reason to believe that these developments have fed on each other over the last quarter century.

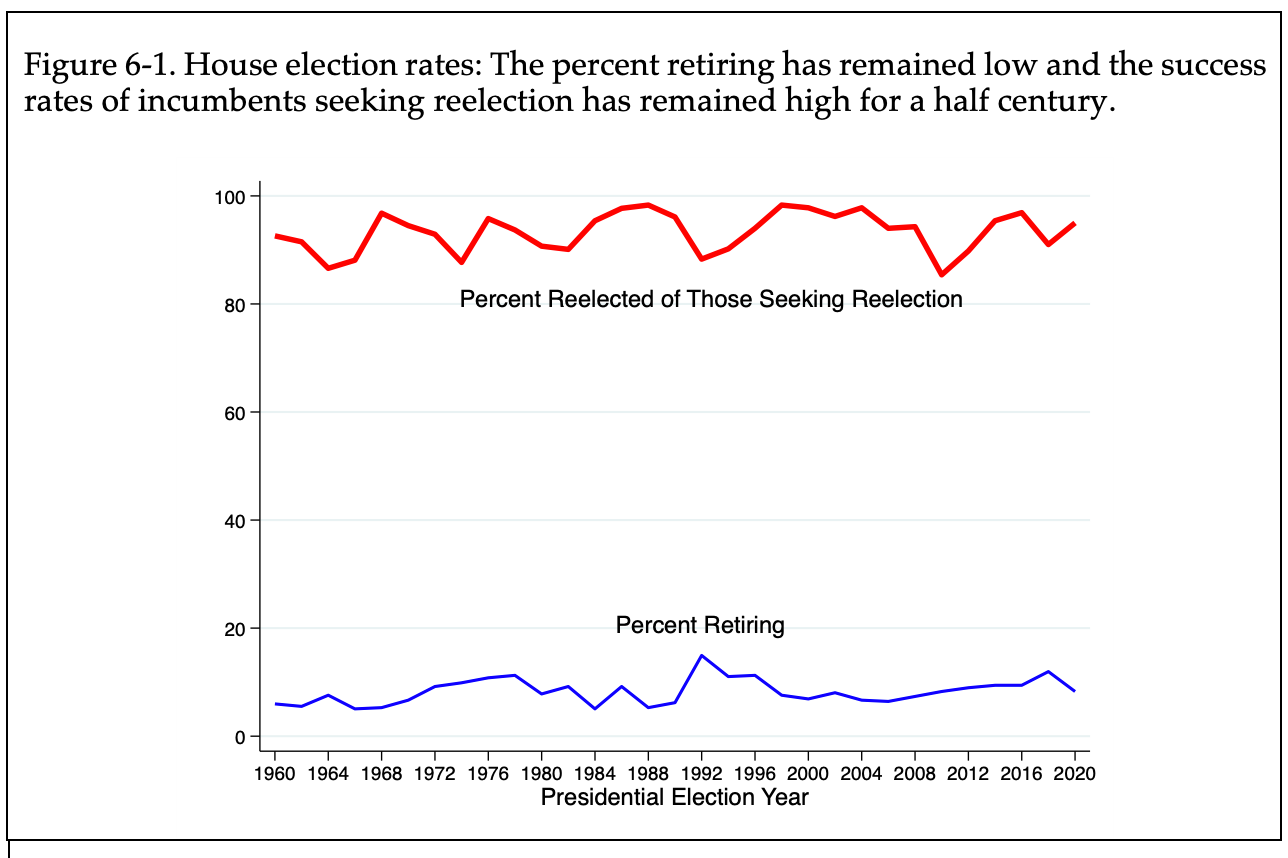

Most members of Congress seek reelection and most succeed. That was true 50 years ago and it remains true (Figure 6-1). At the same time, the number of legislators representing districts that voted for the presidential candidate of the opposite party has plummeted (Figure 6-2). That is, the number of legislators who may experience cross-pressure from their legislative party and their home district has plummeted. Particularly in the South and rural areas, districts once held by Democrats and supported Republican candidates for president in the 1970s and 1980s have elected Republicans to the House with increasing frequency. The pattern is similar in the Senate (data not shown).

One consequence of partisan polarization and the effort of elites, particularly congressional Republicans, to nationalize the issues in congressional elections is the apparent (but potentially misleading) declining strength of incumbency as a factor in determining how voters vote. Judging by Figure 6-1, which shows that retirement and reelection rates have not changed greatly in recent decades, the declining effect of incumbency may be surprising. Well, it is, at least until we take into account that our estimates of the incumbency effect control for party influence. If party labels account for more of the electorates voting decisions, there simply is less variation is outcomes to be explained by incumbency. Incumbency and party have become more fully entwined and reinforcing.

To show the changing values associated with incumbency advantage estimates, I borrow data from political scientist Gary Jacobson.[1] Jacobson modifies a long-used method for estimating the “incumbency effect” that estimates the relationship between a candidate’s share of the vote and being an incumbent, controlling for whether it is a Democrat or Republican that is holding the seat and the presidential vote in the most recent presidential election (a measure of party preferences in the district). The result is what we see in Figure 6-3. To use the technical terms, reports the standardized regression coefficient for the three variables—incumbent (blue line), party (recent presidential vote, black line), and party holding seat (dashed red line). Many analysts interpret the blue line as the strength of the incumbency advantage or “personal vote.”

As for the number of split districts, something different has been happening in the party and incumbency effects since the 1990s. The party effect jumped up in the 1990s and reached very high levels in recent elections. The incumbency effect on outcomes, usually somewhat stronger than the party effect from the 1960s into the new century, declined as the party-outcome relationship strengthened. Other measures that political scientists often use, Jacobson shows, exhibit the same pattern.

An important consequence of these developments is the struggle of moderates in House elections. Moderates are less frequently running for Congress and the advantage that moderates once enjoyed in general election contests has declined substantially.[2] Fewer winning moderate candidates naturally means fewer moderate elected legislators.

These developments in the electoral arena many implications for congressional leaders and their parties in the legislative arena. This is an area ripe for more research, but there are several reasonable implications that are supported by some evidence.

First, and most obvious, this changing pattern directly reinforces the partisan polarization and partisanship in Congress. In each party, fewer members represent districts that lean to the other party and thus are motivated to question strongly partisan and uncompromising strategies. Voices of moderation, if only to raise the electoral implications of immoderate or uncompromising strategies, are quieter in party meetings. Even campaigns for leadership posts seldom involve anyone but strong party supporters—there are few votes to be found among moderates.

The changing electoral context affected leaders’ strategies. The nationalization of elections intensified concern for the party’s national reputation, while the declining number of split districts reduced concern about putting colleagues in a bind. In combination, leaders more freely raised issues, set agendas, and forced votes giving less priority to the electoral interests of a declining number of cross-pressured colleagues and more concern to party interests at stake in legislative battles.

Second, elections altered patterns of party voting. Some background: The House, and to a much lesser degree the Senate, once had a saw-toothed pattern in the frequency of votes that divided the parties—odd-numbered years exhibited more votes generating party divisions than even-numbered years. That is, an election year produced fewer party votes, a pattern that usually was attributed to an effort by the majority party to reduce the number of votes that required its members to choose between the party and their electoral needs. This can be seen in Figure 6-4, which, for each house, shows the percentage of all votes on which at least a majority of one party opposed at least a majority of the other party. For the House, the first and second sessions generally fit the pattern between the 1960s and 1990s. On average, about five percent fewer votes were party votes in the second session than in the first session. A recent study demonstrated that, even within an election year, there is even a tendency for fewer party votes to occur as the election nears.[3] In the Senate, the difference was much smaller and more inconsistent (data not shown).

Something happened in the 1990s. Voting patterns, of course, reflect what issues and motions come to a vote, party and presidential influence, and other factors, in addition to the policy preferences of legislators—so interpreting Figure 6-4 is not a simple matter. In some but not all years, partisan conflict over budgets and spending bills delayed key votes that push more party-line votes to late in a year, yielding a very uneven pattern of party votes over time.

This point is important. The problem for a party leader who wants to protect party colleagues from difficult votes, particularly as an election approaches, is that he or she does not control all of the relevant factors. Most obvious, there are bills that are so essential that they must pass and often are subject to deadlines. Appropriations bills, for example, must be enacted by October 1, the first day of the federal government’s fiscal year. Failure to do so forces federal agencies to shut down, although Congress may pass temporary funding measures (continuing appropriations) to extend the deadline. Approaching debt limits, expiring tax laws, and other issues create situations in which Congress must act to avoid great hardships. Divided party control of the House, Senate, and presidency and Senate filibusters, combined with evenly matched, polarized parties--may stand in the way of agreement on must-pass bills, which forces delays, makes the week-to-week agenda less predictable, creates a game of blame-attribution and blame avoidance, and generates periods of inaction on measures on which the parties are divided and other periods in which one party-line vote follows another for days on end. That has characterizes much of congressional policy making in recent decades.

I would be remiss if I failed to note that Republicans were the beneficiaries of the nationalization of congressional elections and fall-off in split districts. As Jacobson points out, Democrats are concentrated in urban districts and Republicans are distributed more evenly across districts. A greater focus on national party differences undermined a long-term advantage once enjoyed by Democrats who came from a widely diverse set of districts and whose candidates emphasized widely different issues and encouraged a focus on their personal qualities over their national party affiliation. As Gingrich predicted (Note 4), a focus on the differences between the national parties enhanced Republicans’ electoral prospects and contributed to the intense inter-party competition for control of the House.[4]

[1] Gary Jacobson, “It’s Nothing Personal: The Decline of the Incumbency Advantage in U.S. House Elections,” Journal of Politics 77:3 (2015): 861-873 [https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/681670]. Jacobson’s measures are described in his paper.

[2] Andrew Hall, Who Wants to Run? (University of Chicago Press, 2019); Stephen Utych, “Man Bites Blue Dog,” Journal of Politics 82:1 (2020).

[3] René Linstädt and Ryan J. Vander Wielen, “Dynamic Elite Partisanship: Party Loyalty and Agenda Setting in the U.S. House,” British Journal of Political Science 44:4 (2014): 741-772.

[4]Jacobson, op.cit., 871.